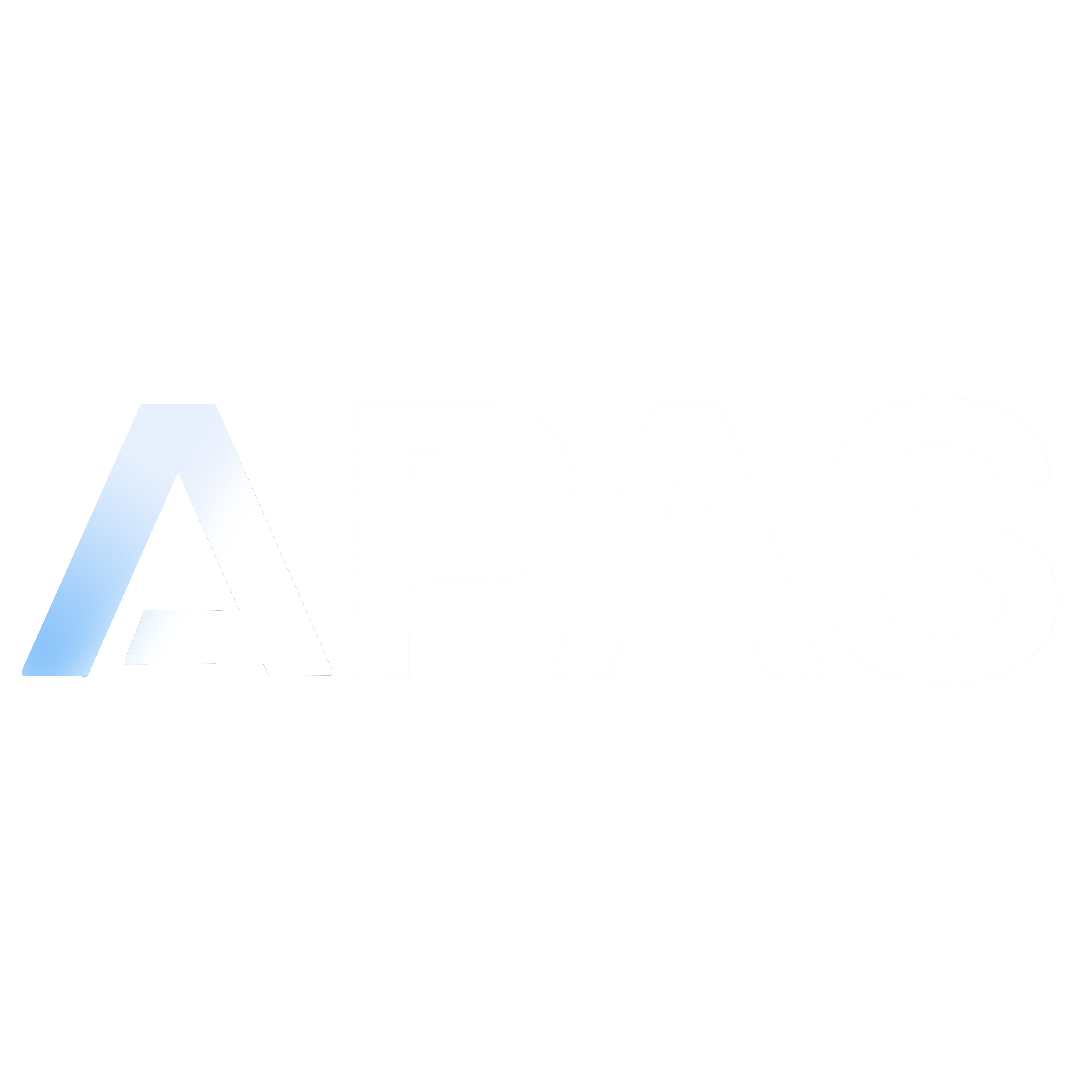

AI Is Both a Shock and a Stress: What a $35 Trillion Warning Tells Us About Infrastructure

$35 trillion.

That's not the value AI might create. It's the wealth that could evaporate if the systems we've built around AI—financial markets, supply chains, labor markets—prove more fragile than we thought.

Harvard economist Gita Gopinath isn't predicting a crash. She's reading a pattern. And if you've ever managed critical infrastructure, the pattern will feel uncomfortably familiar: rapid innovation layered onto aging systems, data trusted without validation, growth concentrated in narrow channels, and governance deferred until after something breaks.

AI isn't creating this fragility. It's exposing it. And in utilities—where invisible value flows through buried pipes, decades-old GIS layers, and fragmented datasets—that exposure is happening right now.

But here's what makes this different from past technology waves:

AI isn't arriving in a vacuum. It's landing on infrastructure systems already crushed by a decade of compounding stresses—aging assets, workforce transitions, climate shocks, regulatory expansion, and chronic underfunding. And unlike those slower-moving challenges, AI demands you adapt at speed.

That's the collision point. And it's why Gopinath's $35 trillion warning isn't just about markets—it's a preview of what happens when the fastest-moving transformation in a generation hits systems operating at the edge of their adaptive capacity.

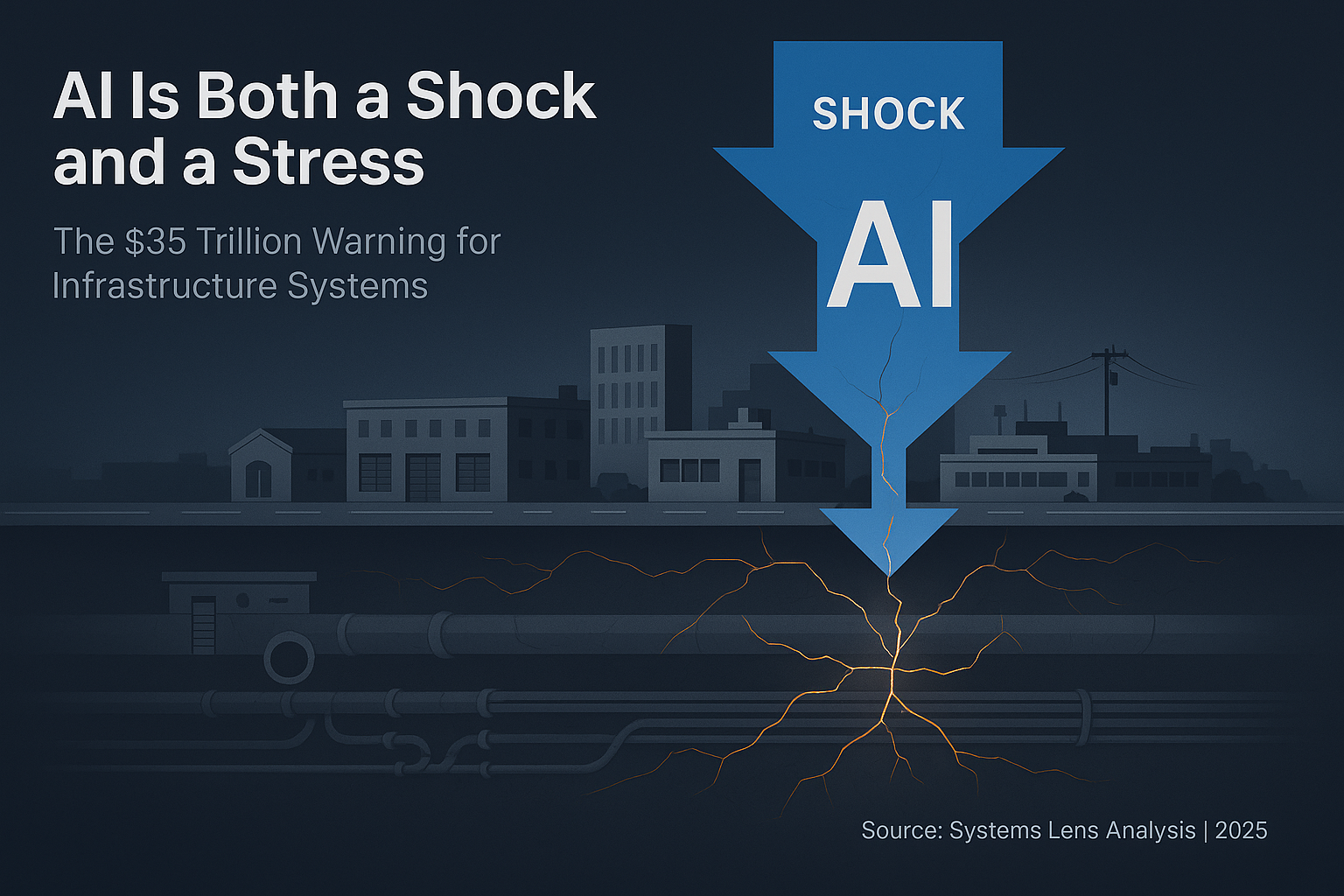

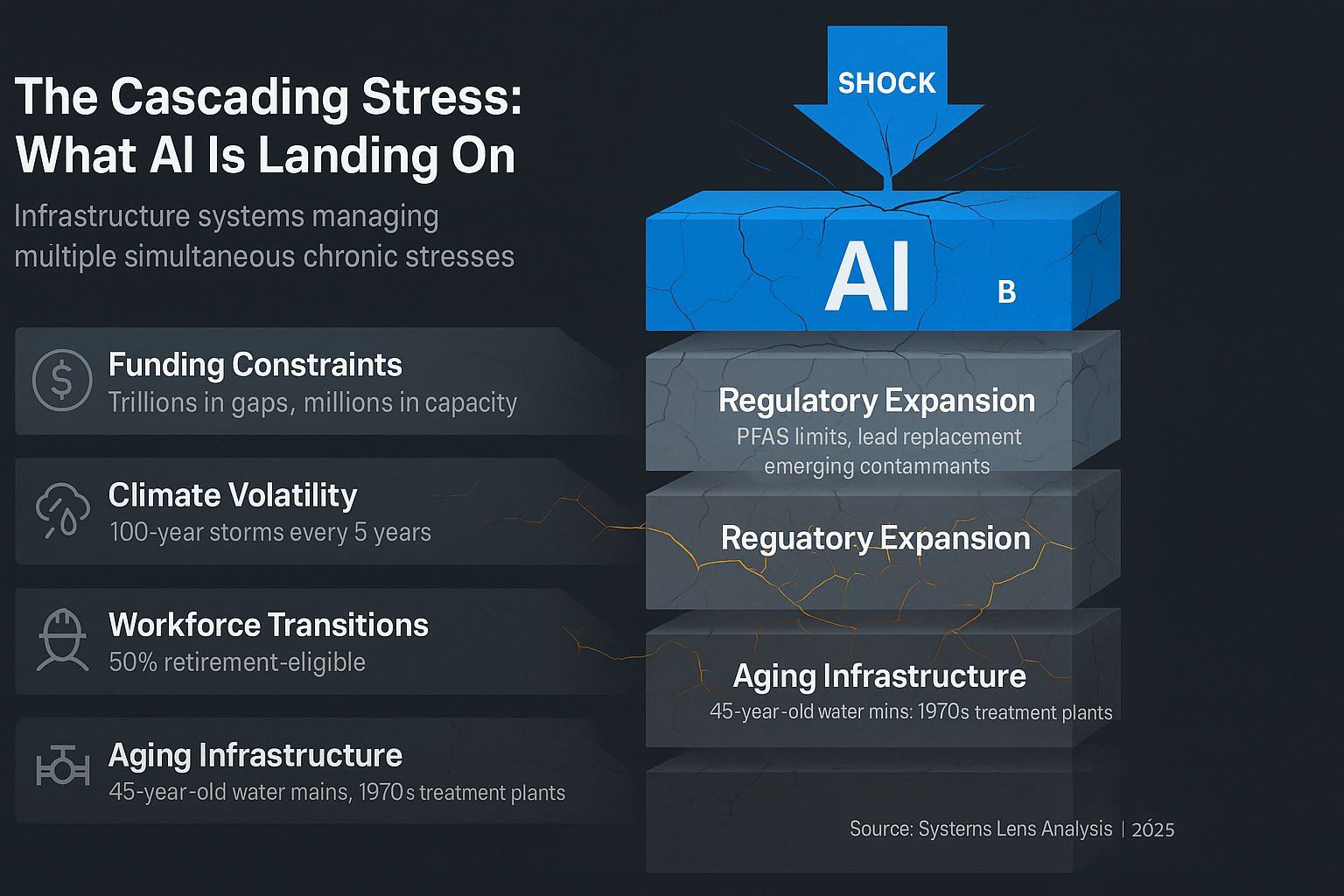

The Cascading Stress: What AI Is Landing On

Before we talk about what AI does to infrastructure, we need to understand what infrastructure is already managing.

Utilities aren't starting from a position of strength. They're managing multiple, simultaneous, chronic stresses—each one demanding resources, attention, and adaptive capacity:

Aging Infrastructure

The average water main in the U.S. is 45 years old. Wastewater treatment plants built in the 1970s are still running on original equipment. Stormwater systems designed for historical rainfall patterns are now handling 100-year storms every five years.

The stress: Every deferred replacement, every temporary fix, every "we'll get to it next budget cycle" decision compounds. The backlog grows. The risk accumulates.

Workforce Transitions

Half of the utility workforce is retirement-eligible within the next decade. The knowledge walking out the door—how this pump behaves in winter, why that valve sticks, which contractor actually shows up—was never documented. It lives in people's heads.

The stress: You can't just hire replacements. The training pipeline is broken. Trade schools closed. Apprenticeship programs got cut. And the complexity of modern systems means new hires need years, not months, to build judgment.

Climate Volatility

Droughts in the Southwest. Atmospheric rivers in California. Flooding in the Midwest. Wildfires disrupting watersheds. Infrastructure designed for 20th-century climate patterns is now operating in conditions it was never engineered for.

The stress: You can't just "adapt." Adaptation requires capital—upgraded stormwater capacity, drought-resilient supply portfolios, wildfire-hardened infrastructure. And climate projections change faster than capital planning cycles.

Regulatory Expansion

PFAS limits. Lead service line replacement. Microplastics monitoring. Emerging contaminants. New stormwater permits. Stricter effluent standards.

The stress: Every new regulation is justified on public health grounds—and most are. But each one adds complexity, monitoring requirements, and capital costs. And the pace of regulatory change is accelerating, not stabilizing.

Funding Constraints

Rates are politically sensitive. Affordability concerns are real. Declining consumption reduces revenue. Debt capacity is finite. Federal and state grant programs are competitive, unpredictable, and insufficient.

The stress: The infrastructure investment gap is measured in trillions. But the political and financial capacity to close that gap moves in millions. The math doesn't work.

Now add AI to this stack.

AI isn't just another initiative competing for attention. It's both a shock and a stress—a sudden disruption that demands immediate response, and a chronic demand for sustained investment in data infrastructure, governance frameworks, workforce training, and organizational capacity.

And here's the critical point: AI doesn't just add to the list of stresses. It amplifies every stress already in the system.

The Amplification Effect: How AI Magnifies Existing Fragility

| Existing Stress | How AI Amplifies It | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Aging Infrastructure | AI optimization models trained on historical failure rates can't predict novel failure modes in 80-year-old pipes. Models assume patterns—but aging infrastructure breaks patterns. | Predictive maintenance AI misses a catastrophic failure because the asset's condition fell outside training data parameters |

| Workforce Transitions | Automation replaces institutional knowledge faster than training programs can rebuild it. The tacit judgment that took decades to develop gets encoded in a model no one can audit. | Work order system automates dispatch based on historical patterns—but those patterns reflected one veteran's judgment, now retired |

| Climate Volatility | AI forecasting models trained on historical climate data fail when "normal" no longer exists. Stormwater capacity planning based on 50 years of rainfall data becomes systematically wrong. | Detention basin sizing algorithm optimizes for historical 100-year storm—which now occurs every 7 years |

| Regulatory Expansion | Compliance automation without governance creates audit risk. Regulators don't accept "the AI missed it" as justification for permit violations. | Automated monitoring system flags false negatives on effluent quality because sensor calibration data was inconsistent |

| Funding Constraints | AI tools require upfront investment in data infrastructure—exactly what's been deferred for decades. You can't automate your way out of data debt. | Utility buys asset management AI but can't use it because GIS, CMMS, and financial systems don't integrate |

This is the pattern Gopinath is describing at the macroeconomic level. But in infrastructure, it's not theoretical—it's operational reality.

When financial markets built on AI-driven trading models face a novel shock, they can halt trading, inject liquidity, or coordinate interventions. Infrastructure systems don't have that luxury. When a pump fails, when a permit lapses, when a storm overwhelms capacity—there's no pause button.

And when AI has been optimizing those systems based on data that doesn't reflect reality? The failure cascades faster than human oversight can respond.

The Setup: When Concentration Becomes Fragility

Let's zoom out to see what Gopinath is tracking in global markets—because the mechanism is identical to what's happening in infrastructure.

OpenAI, which started as a nonprofit in 2015 and launched ChatGPT in 2022, is now preparing for an IPO that could value it at $1 trillion. One of the largest in history.

Nvidia just became the first company ever to hit $5 trillion in market value. Its stock has climbed 12-fold since ChatGPT's launch, driven entirely by AI infrastructure demand.

Over the past decade and a half, U.S. households have poured unprecedented amounts into equities, pushed by big tech's dominance and consistent returns. Foreign investors—especially from Europe—have piled in too, attracted by both the companies and the strength of the dollar.

The result? A massive concentration of global wealth in a narrow slice of the economy.

When that slice wobbles, the shock doesn't stay contained. It radiates—through portfolios, through currencies, through consumption, through GDP.

Gopinath's calculation: a market correction similar to the dot-com crash could wipe out more than $20 trillion in U.S. household wealth—about 70% of America's 2024 GDP. That's several times larger than the losses in 2000.

And the global hit? Another $15 trillion in foreign investor losses, roughly 20% of the rest of the world's GDP.

By comparison, the dot-com crash cost about $4 trillion in today's money.

But here's why this matters for infrastructure:

Utilities face the exact same concentration risk—just at a different scale.

Instead of wealth concentrated in tech stocks, it's operational capacity concentrated in narrow systems: a handful of aging treatment plants, a few critical pump stations, legacy SCADA systems running on outdated software, institutional knowledge concentrated in a shrinking workforce.

When one of those concentrated points fails—and AI accelerates that failure by automating decisions based on bad data—the impact radiates through the entire service area.

AI as Both Shock and Stress

In resilience theory, we distinguish between two types of disruption:

Shocks are sudden: floods, blackouts, recessions, cyberattacks.

Stresses are chronic: underinvestment, workforce decline, aging infrastructure, regulatory uncertainty.

AI now represents both.

| Dimension | How AI Acts | Infrastructure Example |

|---|---|---|

| Shock | Sudden displacement or system failure | Automated work order system causes cascade of deferred maintenance; model error triggers regulatory violation; workforce displacement happens faster than retraining capacity |

| Stress | Chronic demand for new capacity | Sustained investment in data infrastructure; ongoing governance framework development; continuous workforce training; persistent organizational adaptation |

The Labor Channel

Gopinath points to research showing that nearly 90% of automation-related job losses in the U.S. since the mid-1980s occurred in the first year of recessions.

Here's the pattern: firms invest in automation when times are good and profits are high. They keep workers on. But when margins tighten, they use that automation to cut costs—fast.

AI changes the scale. It doesn't just threaten routine tasks. It threatens cognitive, higher-skill roles: analysts, engineers, planners, compliance officers.

Gopinath estimates:

- 30% of jobs in advanced economies are at risk of AI-driven replacement

- 20% in emerging markets

- 18% in low-income countries

For utilities, this isn't just about headcount. It's about institutional memory, judgment, and context—the things that don't show up in a training dataset.

When you automate a process that depends on decades of local knowledge, you're not just replacing a person. You're replacing a decision-making capacity that was never fully documented.

The veteran operator who knows that pump sounds different before it fails? That knowledge doesn't transfer to an AI model trained on maintenance logs.

The engineer who understands why a particular pipe segment has unique corrosion characteristics because of soil conditions and installation history? That context gets lost when asset management is automated based on generalized condition assessment protocols.

This is why workforce displacement in utilities isn't just a labor issue—it's an operational fragility issue. Every person who leaves takes irreplaceable systems knowledge with them. And AI, rather than capturing that knowledge, often accelerates its loss by creating the illusion that automation can replace judgment.

The Finance Channel

Before the AI boom, financial systems already relied on automated models for trading, risk assessment, and portfolio management. Now those models are being replaced by self-learning, black-box AI systems whose logic even experts struggle to interpret.

Gopinath highlights a specific risk: herding behavior.

If many AI models are trained on similar data and respond to the same signals, they could trigger simultaneous shifts—everyone selling the same assets, chasing the same safe havens, amplifying volatility instead of dampening it.

And because the models are opaque, diagnosing and correcting that behavior in real time becomes nearly impossible.

For utilities, the analog is clear: if everyone adopts the same vendor's AI tool, trains it on the same incomplete datasets, and automates the same processes, you're not diversifying risk—you're synchronizing it.

Think about what this means in practice:

- Multiple utilities in a region use the same asset management AI platform

- All trained on similar data: historical work orders, industry-standard condition assessment protocols, generalized failure rate models

- When the model produces a systematic error—say, underestimating corrosion risk in a particular pipe material under specific soil conditions—that error propagates across every utility using the platform

One bad model assumption could cascade through dozens of systems before anyone notices. And by the time they do, deferred maintenance decisions have compounded for years.

This is synchronized regional fragility, not isolated utility risk.

The Supply Chain Channel

Utilities increasingly rely on AI-powered forecasting tools to manage procurement, inventory, and maintenance schedules. In normal times, these tools boost efficiency.

But when they're trained on outdated or incomplete information, they produce costly forecasting errors.

Think about what happened during COVID: supply chain disruptions rippled for years because systems weren't designed to handle novel shocks. Lead times that were historically 6-8 weeks suddenly stretched to 6-12 months. Components that were always available became unobtainable.

AI could make those swings faster and more damaging by automating procurement decisions based on patterns that no longer apply.

Gopinath warns that AI performs poorly when faced with conditions different from the data it was trained on. And in infrastructure, the operating environment is always changing:

- Climate patterns (more extreme weather, longer droughts, larger floods)

- Regulatory regimes (new contaminant limits, stricter permit requirements)

- Material availability (supply chain disruptions, manufacturing shifts)

- Workforce capacity (retirements, training pipeline gaps)

If your AI is making critical decisions based on historical averages in an environment defined by accelerating change, you're not building resilience. You're codifying brittleness.

The Stormwater Example: AI Meets Complexity

Let me make this concrete with a system I know well: stormwater management.

Stormwater systems are some of the most complex, least visible, and most underfunded pieces of infrastructure in the U.S. They involve:

- Hydrology: rainfall patterns, runoff coefficients, peak flows

- Hydraulics: pipe capacity, detention basin sizing, outlet structures

- Regulatory compliance: MS4 permits, TMDL limits, NPDES monitoring

- Asset management: condition assessment, maintenance records, capital planning

- Finance: stormwater fees, debt service, rate structures, grant eligibility

Now imagine deploying an AI tool to "optimize" stormwater infrastructure. What does that even mean?

- Does it prioritize flood risk reduction? Water quality? Cost efficiency? Equity?

- Is it trained on local rainfall data, or regional averages?

- Does it account for climate projections, or just historical patterns?

- Can it distinguish between a pipe that's structurally sound but hydraulically undersized?

- Does it understand that a detention pond isn't just an asset—it's a regulatory compliance mechanism tied to a permit that expires in five years?

Here's where the cascading stress becomes visible:

The AI needs clean rainfall data—but the rain gauge network has gaps. Some gauges failed years ago and were never replaced (funding stress). Historical data exists in multiple formats across different systems (data fragmentation). Climate projections show increasing intensity, but translating that into design standards requires engineering judgment, not just statistical modeling (workforce capacity).

The AI needs accurate asset condition data—but inspection records are incomplete (deferred maintenance), asset IDs are inconsistent between GIS and CMMS (data silos), and condition ratings were assigned by different inspectors using different criteria over 20 years (institutional knowledge loss).

The AI needs integrated regulatory context—but permit requirements have changed three times in the past decade (regulatory expansion), compliance monitoring data lives in a separate database (data fragmentation), and the engineer who understood how all the pieces fit together retired last year (workforce transition).

If the data feeding that AI model is inconsistent—if your GIS doesn't match your CMMS, if your hydraulic model hasn't been calibrated in a decade, if your inspection records are incomplete—the AI won't flag those gaps. It will work around them.

And the recommendations it produces will look authoritative. They'll be fast. They'll be detailed. They'll come with risk scores and confidence intervals.

And they'll be wrong in ways that won't become obvious until the next 100-year storm—or the next audit.

This is the danger Gopinath is describing at the macroeconomic level. But it's playing out right now, in real time, in infrastructure systems across the country.

The Pattern Across Utilities: When AI Meets Data Reality

Here's what happened in practice when utilities deployed AI-driven predictive maintenance.

A wastewater treatment facility piloted an AI system to predict equipment failures. The success story sounds promising: they saved approximately $45,000 by preventing a major equipment failure during a six-month pilot—enough to pay for roughly two years of the predictive maintenance service.

But that headline obscures the reality behind implementation.

Data Quality: The Foundation That Crumbles

Many utilities discovered their historical data was sparse, inconsistent, or unusable. Sensor readings had gaps. Failures weren't logged with precise timestamps. Different pumps measured different parameters. For utilities with decades-old equipment and limited sensor infrastructure, this presented a significant hurdle.

The problem compounds: some types of failures are so rare—a pump might fail catastrophically only once in 10 years—that machine learning systems struggle to statistically learn these patterns.

This is "garbage in, garbage out" at scale. The AI can only learn from the data it's fed. If your maintenance logs are incomplete, your sensor data is inconsistent, and your failure records are missing context—the model won't flag those gaps. It will just produce unreliable predictions.

The Complexity Challenge

Water and wastewater systems operate under highly variable conditions. Wastewater pump stations experience widely fluctuating flows and loads depending on time of day or weather events, which can confound predictive models.

One case study found it "extremely difficult" to get clear indication for cleaning aeration equipment because of numerous influencing variables like pH, temperature, and time of day.

Translation: The AI struggles to distinguish whether a change in performance indicates a developing fault or just normal operational variation.

For stormwater systems, this problem intensifies. Detention basins that sit dry most of the year. Pumps that only activate during storm events. Assets whose "normal" behavior changes seasonally, by rainfall pattern, by land use development upstream.

If the operating environment is always changing, historical patterns become less predictive—and AI trained on those patterns becomes less reliable.

The Timeline Reality: Not "Plug and Play"

Contrary to marketing claims, there's substantial lead time to set up, integrate, and train these systems. Most utilities report needing 6-12 months of data gathering just to establish baseline equipment behavior. Achieving a high-confidence, reliable prediction system typically takes 1-2 years from project kickoff.

This is the 12-24 month implementation reality. It's not AI failure—it's the time required to clean data, integrate systems, establish baselines, and validate predictions.

And that timeline assumes you have the data infrastructure in place. For utilities with legacy systems, getting data out of decades-old equipment or adding sensors to old assets can be technically challenging. Data silos pose problems: maintenance data might reside in a separate database from operations data.

Without extensive IT integration projects, the predictive maintenance tool lacks the full context needed for accurate predictions.

False Alarms and Eroded Trust

Predictive models inevitably produce false positives—predicting failures that don't happen—and false negatives—missing actual failures. Early in deployment, false alarms are often frequent as the system learns. If not managed properly, this erodes trust: maintenance crews start ignoring warnings.

This is the "boy who cried wolf" effect at organizational scale.

No system achieves the 99% accuracy sometimes promised in marketing materials. A more realistic expectation is a significant reduction in unplanned outages—perhaps 50-70%—but not elimination of all failures.

That gap between marketed promises and operational reality creates political problems. Leadership expects the 99% accuracy they saw in vendor presentations. Operations deals with the 30% false alarm rate. When the expectations don't match reality, support for the initiative weakens.

The Workforce Dimension

Introducing AI into a traditionally mechanical/electrical maintenance department faces human challenges. Staff may distrust a "black box" algorithm or fear that AI will replace jobs. Additionally, existing technicians might lack experience interpreting data trends or understanding predictive algorithms.

But here's the critical insight: Contrary to marketing claims that "the AI does it all," successful implementations require seasoned operators and maintenance engineers to be deeply involved to train, validate, and guide the AI system. AI augments human decision-making; it doesn't replace the need for skilled personnel who understand why equipment might be failing.

This is exactly backward from how most utilities approach AI deployment.

The assumption: buy the tool, deploy it, let it run, reduce headcount.

The reality: AI requires more skilled workforce capacity, not less—people who can interpret model outputs, validate predictions against operational context, and correct the system when it's wrong.

When you're already managing workforce transitions, retirements, and skills gaps, adding AI doesn't reduce that pressure. It amplifies it.

What This Pattern Reveals

These aren't isolated failures. They're systemic patterns that reveal the exact fragility Gopinath warns about:

AI amplifies whatever system quality already exists.

- If your data is clean, integrated, and governed → AI can optimize operations and predict failures accurately

- If your data is fragmented, inconsistent, and ungoverned → AI will codify those problems at scale and make bad decisions faster

The utilities that succeeded had already done the 50 steps back:

- They'd invested in sensor infrastructure

- They'd cleaned and integrated their data systems

- They'd trained their workforce to interpret AI outputs

- They'd set realistic expectations about timelines and accuracy

- They'd built governance frameworks to validate predictions

The utilities that struggled skipped those steps and tried to go directly to automation.

The result? Not transformation—expensive learning curves measured in years, not months.

This is the same pattern playing out in financial markets, supply chains, and labor markets. When AI meets fragile systems, it doesn't make them stronger. It exposes how brittle they already were.

And in infrastructure—where you can't pause operations to fix the data—that exposure becomes operational risk.

The 50/500 Principle: Why Slowing Down Is the Only Way to Speed Up

Here's the central tension utilities face:

The external pressure is to move fast. Regulators expect AI-enabled compliance. Ratepayers expect efficiency. Vendors promise transformation. Industry conferences showcase "digital leaders." The message is clear: adopt AI now or get left behind.

But the internal reality is fragmented systems, inconsistent data, stretched capacity, and limited governance bandwidth.

When you deploy AI into that environment without addressing the underlying fragility, you don't get transformation. You get amplified dysfunction at the speed of automation.

This is where the 50/500 Principle becomes critical:

Take 50 steps back to go 500 steps forward.

What "50 Steps Back" Means

1. Data Integrity First

Before you automate anything, audit your data:

- Are asset IDs consistent across GIS, CMMS, and financial systems?

- Do inspection records match physical assets?

- Are failure codes standardized and meaningful?

- Does historical data reflect actual conditions, or just what got logged?

This isn't glamorous. It's expensive. It requires cross-departmental coordination. It surfaces problems that have been ignored for years.

But without it, every AI tool you deploy will inherit those problems—and scale them.

2. Workforce Readiness, Not Displacement

AI will change jobs. That's inevitable. But how it changes them depends entirely on whether you prepare your workforce or just automate around them.

Preparation means:

- Identifying which roles will be augmented vs. replaced

- Creating pathways for people to transition into new roles (data analysts, AI system monitors, governance specialists)

- Giving staff latitude to experiment with AI tools in low-stakes environments

- Building feedback loops so operators can flag when models are wrong

This only happens if leadership creates the space for it. You can't bolt AI training onto existing workloads and expect adaptation. You need dedicated time for learning, experimentation, and skill development.

That's a resource commitment—headcount, budget, time. Most utilities don't have slack capacity. Which means making this a priority requires deprioritizing something else.

That's hard. But the alternative—automating first and dealing with workforce disruption later—is what creates the labor channel risk Gopinath warns about.

3. Governance Before Deployment

AI governance isn't just a policy document. It's an operational framework that answers three questions for every AI tool:

- What decision is this making? (and is that a decision we want automated?)

- What data is it using? (and have we validated that data?)

- Who is accountable when it's wrong? (and how do we detect errors in real time?)

Most AI deployments skip these questions because they feel like bureaucratic friction. But they're the only thing standing between "AI-enabled optimization" and "automated liability."

4. Regional Coordination, Not Isolated Adoption

Here's where most utilities miss the bigger picture:

AI governance can't be solved utility-by-utility. It requires regional coordination.

Why?

- Data interoperability: If every utility in a watershed uses different asset management platforms with incompatible data standards, regional planning becomes impossible.

- Workforce ecosystems: If AI displaces 15% of technical staff across a region, individual utilities can't absorb that displacement alone. You need regional training programs, apprenticeship pipelines, and transition support.

- Procurement standards: If utilities adopt different AI tools without coordination, you create synchronized regional risk—multiple systems vulnerable to the same vendor dependencies, model errors, or cybersecurity threats.

- Shared infrastructure for data governance: Building clean, interoperable data systems is expensive. But it's a regional asset, not just a utility cost. Shared investment in data infrastructure—standardized taxonomies, interoperable platforms, regional data trusts—distributes the cost and multiplies the value.

This is the difference between "change management" and "systems transformation."

Change management focuses on getting one organization to adopt a new tool. Systems transformation recognizes that utilities operate in regional ecosystems—shared watersheds, interconnected supply chains, overlapping regulatory frameworks, common workforce pipelines.

When one utility's AI fails, it doesn't just affect their ratepayers. It creates ripple effects across the region.

That's why governance has to be coordinated. Not centralized—coordinated. Which means:

- Regional forums for sharing lessons learned (what worked, what failed, what data quality issues surfaced)

- Shared procurement standards (interoperability requirements, vendor accountability frameworks)

- Workforce development consortia (training programs designed for regional needs, not individual utilities)

- Data infrastructure treated as regional public goods (like roads or broadband—everyone benefits, so everyone invests)

What "500 Steps Forward" Looks Like

When you take the 50 steps back—clean data, workforce readiness, governance frameworks, regional coordination—then AI becomes transformative.

You can:

✅ Predict failures accurately because your models are trained on validated data that reflects actual asset conditions

✅ Optimize operations intelligently because your workforce understands why the AI recommends certain actions and can override when context demands it

✅ Respond to climate shocks faster because your systems integrate real-time data, climate projections, and regulatory requirements into a coherent decision framework

✅ Demonstrate compliance confidently because every automated decision is traceable, auditable, and tied to accountable humans

✅ Make capital planning defensible because your asset data, financial models, and risk assessments are interoperable and transparent

✅ Build regional resilience because utilities share data standards, workforce capacity, and governance best practices

This is the 500 steps forward. Not just faster processes—more resilient systems.

The Cost of Skipping the 50 Steps

What happens if you skip the preparation and deploy AI fast?

You get the pattern utilities experienced: authoritative-looking recommendations that compound bad data into worse decisions. Six to twelve months just establishing baseline equipment behavior. One to two years before achieving reliable predictions. False alarm rates that erode workforce trust. Integration challenges with legacy systems that take months to resolve.

You get automation as a liability shield—a way to deflect accountability ("the system recommended it") without improving outcomes.

You get workforce disruption without transition pathways—people displaced faster than training programs can adapt.

You get synchronized regional failure—multiple utilities vulnerable to the same model errors, vendor dependencies, or data quality issues.

And you get regulatory exposure—because when the AI misses a permit violation or defers critical maintenance, regulators don't accept "the algorithm said so" as justification.

The irony is that moving fast without data integrity, workforce readiness, and governance doesn't actually save time. It just frontloads risk that you'll pay for later—with interest.

The Three Questions Every Leader Should Ask

Gopinath offers three policy directions designed to reduce the chances that AI amplifies the next crisis. I've adapted them for infrastructure—and added the political reality behind each one.

1. What exactly are we automating?

Not every process should be automated. Some require judgment, context, and accountability that can't be encoded.

Before deploying AI, ask:

- What decision is this tool making?

- What data is it using?

- What assumptions is it built on?

- Who is accountable when it's wrong?

Why this gets skipped:

Urgency bias. Vendor pressure. The assumption that "smart people built it, so it must be smart." And the uncomfortable truth that questioning an AI tool can feel like questioning progress itself.

In utilities, automation without governance becomes institutional risk. Because when something breaks, the regulator doesn't accept "the algorithm said so" as an answer.

Action step:

Before any AI deployment, conduct a decision audit: map every decision the tool will make, identify the data inputs, document the accountability chain, and define error detection mechanisms. If you can't complete this audit, you're not ready to deploy.

2. What data are we trusting?

AI is only as good as the data it's trained on. And in infrastructure, data quality is almost always worse than we think.

Key steps:

- Audit data sources for completeness, accuracy, and consistency

- Integrate siloed datasets (GIS, CMMS, financial systems, regulatory databases)

- Build feedback loops so models can be corrected when reality diverges from prediction

Why this gets skipped:

Because data governance is expensive, unglamorous, and politically difficult. It requires cross-departmental coordination, budget for cleanup, and the willingness to admit that legacy systems are broken.

It's easier to buy an AI tool and hope it "figures it out" than to invest two years in data infrastructure. But that's the choice that creates the 12-24 month learning curve utilities experienced.

If your data isn't interoperable, your AI isn't intelligent—it's guessing.

And in a rate case, in an audit, in a bond issuance, guessing has a price.

Action step:

Before deploying AI, conduct a data integrity assessment: sample 100 records from each critical system, check for consistency across platforms, measure error rates, and estimate the cost of cleanup. If error rates exceed 5%, pause AI deployment and fix the data first.

3. Who is accountable when AI is wrong?

This is the governance question most organizations skip.

When an AI tool recommends deferring maintenance on a pump, and that pump fails, who's responsible? The vendor? The utility? The engineer who signed off? The model?

Why this gets skipped:

Because accountability is uncomfortable. It creates liability. It slows decisions. And in organizations where responsibility is already diffuse, adding AI creates a convenient buffer: "The system recommended it."

But without clear accountability structures, AI becomes a liability shield—a way to deflect responsibility instead of improving outcomes.

Here's what accountability looks like in practice:

- Every AI-generated recommendation must be reviewed by a named human who signs off on the decision

- Error detection mechanisms must be built into the system (e.g., if an AI defers maintenance on a critical asset, a supervisor reviews the recommendation)

- Audit trails must be maintained: what data was used, what the model recommended, who approved it, what the outcome was

- Feedback loops must exist: when the model is wrong, the error is logged, analyzed, and used to retrain or recalibrate

Action step:

Before any AI deployment, create an accountability matrix: for each type of decision the AI will make, identify who reviews it, who approves it, who audits it, and who's responsible if it fails. If any cell is blank, the system isn't ready.

Gopinath emphasizes that governance isn't about slowing innovation. It's about ensuring innovation survives the next shock.

In utilities, that shock could be a flood, a regulatory audit, a bond rating review, or a workforce transition. If your AI governance can't handle those stresses, it's not governance—it's paperwork.

Regional Governance or Regional Fragility: The Choice Utilities Face

Here's the hard truth most utilities are avoiding:

You can't solve AI governance in isolation. This requires regional coordination—or you're building synchronized regional fragility.

Why?

1. Workforce Disruption Doesn't Respect Utility Boundaries

If AI displaces 15% of technical staff across a metropolitan region, individual utilities can't absorb that shock alone.

Where do those workers go? Who retrains them? Who funds the transition?

Without regional coordination, you get:

- Loss of institutional knowledge across multiple utilities simultaneously

- Competition for a shrinking pool of qualified workers

- Training programs misaligned with actual regional needs

- Political backlash when job losses concentrate in specific communities

With regional coordination, you build:

- Shared apprenticeship and training pipelines

- Career transition programs that move workers into new roles (data analysts, AI system monitors, compliance specialists)

- Regional workforce ecosystems that distribute capacity across utilities

- Political buy-in because the transition is managed proactively, not reactively

This isn't charity. It's systems thinking. Because when neighboring utilities lose technical capacity, your mutual aid agreements become worthless. Regional resilience depends on distributed capacity.

2. Data Silos Create Regional Blind Spots

Every utility in a watershed affects the others. Upstream discharge affects downstream water quality. Regional stormwater systems are interconnected. Shared aquifers don't respect jurisdictional boundaries.

But if every utility's data is siloed—incompatible formats, inconsistent taxonomies, proprietary platforms—regional planning becomes impossible.

Example: A regional climate adaptation plan requires understanding flood risk across a metropolitan area. That means integrating:

- Stormwater capacity data from 12 municipalities

- Asset condition data from 8 utilities

- Rainfall projections from 3 climate models

- Land use data from 15 planning departments

- Regulatory requirements from 2 state agencies

If none of those datasets are interoperable, the "regional plan" is just 12 disconnected utility plans stapled together.

And when AI tools get deployed on top of that fragmentation? You're automating regional incoherence.

The alternative: treat data infrastructure as a regional public good.

Just like roads, broadband, or emergency response systems, data infrastructure benefits everyone—so everyone invests.

This means:

- Shared data standards: common taxonomies, interoperable formats, open APIs

- Regional data trusts: shared platforms where utilities can securely exchange data while maintaining operational control

- Coordinated procurement: interoperability requirements built into vendor contracts

- Joint investment: shared funding for data governance, cleanup, and infrastructure

This isn't about centralization. It's about interoperability. Utilities maintain control of their data—but commit to standards that enable regional coordination.

3. Synchronized AI Risk Requires Coordinated Mitigation

If 10 utilities in a region all adopt the same AI platform, trained on similar datasets, using the same vendor's model architecture—you haven't diversified risk. You've synchronized it.

One model error propagates across all 10 systems. One vendor failure affects the entire region. One cybersecurity vulnerability creates 10 entry points.

This is the finance channel risk Gopinath warns about—but in infrastructure, the stakes are higher. Because when financial markets face synchronized risk, they can halt trading. Infrastructure can't pause.

Coordinated mitigation means:

- Vendor diversity: avoid regional dependence on single platforms

- Model transparency requirements: procurement standards that require vendors to document model assumptions, training data, and error rates

- Shared error tracking: regional forums where utilities report AI failures, model errors, and governance lessons learned

- Mutual aid protocols: when one utility's AI system fails, neighbors can provide operational support because they understand the regional context

This only works if utilities treat governance as a collective challenge, not a competitive advantage.

4. Procurement Power Increases with Regional Coordination

Individual utilities have limited leverage with AI vendors. But a regional procurement consortium has scale.

That scale translates to:

- Interoperability requirements: vendors must meet regional data standards or they don't get the contract

- Accountability frameworks: vendors must provide audit trails, error detection mechanisms, and governance documentation

- Performance guarantees: contracts tied to measurable outcomes, not just tool deployment

- Shared risk: regional consortia can negotiate liability terms that individual utilities can't

This isn't about bureaucracy. It's about ensuring that AI tools serve utilities—not the other way around.

The Data-to-Decision Chain

Everything in a utility is connected through data:

- Metering → Billing → Revenue

- Assets → Maintenance → Capital planning

- Permits → Compliance → Funding eligibility

When data is inconsistent, every downstream decision weakens.

This isn't an IT issue. It's an economic fragility.

In financial markets, a loss of confidence erases wealth overnight. In utilities, a loss of clarity erodes value just as fast—through inefficiency, delays, lost revenue, and eroded public trust.

Think of it this way:

If a utility can't prove its assets are being maintained according to a defensible standard, it can't justify rate increases. If it can't justify rates, it can't fund capital improvements. If it can't fund improvements, assets deteriorate faster. If assets deteriorate, service declines. If service declines, trust erodes. If trust erodes, political support weakens. And the cycle accelerates.

AI can either help break that cycle—or accelerate it.

The difference comes down to whether the data feeding those systems reflects reality—or just the limitations of the systems that produced it.

What Real Resilience Means

Resilience isn't a buzzword. It's an operational property: the ability to absorb disruption without collapse.

That requires:

- Transparent, interoperable data that connects assets, operations, finance, and compliance

- Financial discipline across both O&M and capital, with clear traceability from spending to outcomes

- Regulation tied to measurable outcomes, not just process compliance

- Teams trained to interpret, not just implement, AI—so they can recognize when a model is wrong

- Regional coordination that treats data infrastructure, workforce capacity, and governance as shared investments

"Automation doesn't eliminate inefficiency—it codifies it."

If your current system is fragmented, adding AI won't fix it. It will scale the fragmentation.

But if you use AI to fix the data debt inside your systems—to connect silos, validate assumptions, and build feedback loops—then you can finally build infrastructure that is both intelligent and accountable.

Lessons from the Bigger Economy

The global economy depends on a narrow base of technologies. Utilities depend on a narrow base of revenue and expertise.

Both need diversification—not in branding, but in capacity.

Gopinath argues that the world needs more balanced growth: if other regions like Europe or emerging markets can strengthen their own economic engines, it reduces global fragility.

For utilities, the analog is clear: diversify your decision-making capacity.

- Don't rely on a single vendor's AI tool

- Don't train all your models on the same narrow dataset

- Don't automate every process just because you can

- Don't let efficiency optimization crowd out resilience planning

- Don't treat AI governance as a utility-level problem when it's a regional-systems challenge

Innovation for speed without innovation for stability is just another race toward collapse.

Where Utilities Go from Here

The most resilient utilities of the next decade won't be the biggest or the most digital.

They'll be the most coherent.

Data, finance, and governance will operate as one integrated structure. Every permit, every invoice, every maintenance record becomes a dataset that reinforces trust—not just with regulators, but with ratepayers, bondholders, and the next generation of engineers.

AI can help connect those dots. But it will also expose every gap.

The difference will depend on whether we've designed our systems to learn with integrity.

And whether we've recognized that infrastructure systems—like financial markets—are too interconnected for isolated governance to work.

Final Thought: The Question No One's Asking

AI is both a shock and a stress.

It's a shock because it demands immediate adaptation—deploy now or fall behind. It disrupts workflows, displaces workers, and forces decisions at speed.

It's a stress because it requires sustained investment in exactly the capacities utilities have been deferring for decades: data infrastructure, workforce development, governance frameworks, regional coordination.

And it's landing on systems already crushed by compounding stresses: aging infrastructure, workforce transitions, climate shocks, regulatory expansion, and chronic underfunding.

But this is also an opportunity.

If we use AI to fix the data debt inside our systems—not just to automate it—we can finally build infrastructure that is intelligent, accountable, and resilient.

The outcome will depend not on the intelligence of our models, but on the integrity of our systems.

So here's the question:

When your next capital plan assumes AI will optimize asset management, or streamline compliance, or improve forecasting—who in the room is asking what happens when the model is wrong?

Who's asking whether the workforce is ready? Whether the data is validated? Whether accountability is defined? Whether regional coordination exists?

If the answer is no one, you're not adopting AI.

You're inheriting risk.

And when that risk materializes—when the pump fails, the permit lapses, the forecast misses, the rate case stumbles—you won't be able to blame the algorithm.

Because the algorithm was never the problem.

The system was.

And unlike financial markets, infrastructure systems don't get bailouts. They just fail—slowly, incrementally, and irreversibly—until someone takes 50 steps back to fix the foundations.

The utilities that do that work now will be the ones still operating a decade from now.

The ones that don't will become case studies in what Gopinath is warning us about: what happens when the fastest transformation in a generation hits systems built for a different era.

Key Takeaways

✓ AI isn't arriving in a vacuum—it's landing on systems already managing aging infrastructure, workforce transitions, climate shocks, regulatory expansion, and funding constraints

✓ AI amplifies existing stresses—it doesn't just add to the list, it magnifies every fragility already in the system

✓ The 50/500 Principle: Take 50 steps back (data integrity, workforce readiness, governance, regional coordination) to go 500 steps forward (actually resilient AI-enabled systems)

✓ Real implementation timelines: 6-12 months for data baseline, 1-2 years for reliable predictions, not the "plug and play" vendors promise

✓ Governance must be regional, not just organizational—workforce disruption, data fragmentation, and AI risk don't respect utility boundaries

✓ Data quality is economic stability—inconsistent data erodes value through inefficiency, lost revenue, and regulatory exposure

✓ Ask the hard question: Who's accountable when the AI is wrong? If no one can answer, you're not ready to deploy

✓ Workforce reality: AI requires more skilled capacity, not less—people to interpret, validate, and correct models

✓ Automation without integrity codifies dysfunction—if you skip data cleanup and governance to move fast, you're just scaling existing problems at speed

✓ Infrastructure resilience requires coherence—connecting data, finance, operations, and governance into one integrated, regionally-coordinated structure

Welcome to The Systems Lens—where we don't fix symptoms. We redesign systems.